Last week in Boulder, I took my Bodhisattva vows at the end of a weeklong Planetary Dharma retreat. On the third day, just a block from our retreat site, in an act of intense violence and hatred, a radicalized man threw a molotov cocktail at peaceful protesters rallying for Israeli hostages in Gaza. One person was burned from head to toe. Others were injured. The air thickened with sirens, smoke, and fear.

I walked a different route to lunch that day, bypassing the site of the chaos. Many of my Sangha mates were present just moments after the man threw the bomb. Soon after, the police evacuated our retreat building. Our group dispersed—some to Airbnbs, others to hotels or nearby homes—and gathered later on Zoom to process what had happened. We shared what we’d seen, how it had impacted us. Then we sat together in a guided meditation. Silence mixed with heartfelt words. A shared prayer.

That day reminded me: we are not always safe on the relative level. Cars crash. Fires consume. Viruses kill. Humans hurl molotov cocktails, insults, and fists. Sometimes danger arrives with drama; sometimes it’s quiet and chronic—like the slow erosion of health through aging, or the nervous wear from decades of cultural or familial trauma.

And yet, as I sat in meditation, I noticed something else. Despite that abhorrent act of violence, a deep sense of safety remained in me. Not because I shut out what had happened. Not because I felt protected from harm. But because I had access to something deeper. My body still registered tension mixed with sadness—tight chest, heightened alertness, heavy heart. But underneath it all, there was ground. There was calm. There was a knowing.

My teacher, John Churchill, calls this fundamental safety.

The idea sounds religious—reminiscent of teachings that promise safety through an afterlife, a divine protector, a continuation beyond death. Perhaps that's some of it. I recognize that we are woven into the fabric of a far greater mystery than we will ever comprehend. But the kind of safety I’ve come to know through meditation is not dogmatic. It’s not even conceptual. It’s somatic. It’s real. It’s felt.

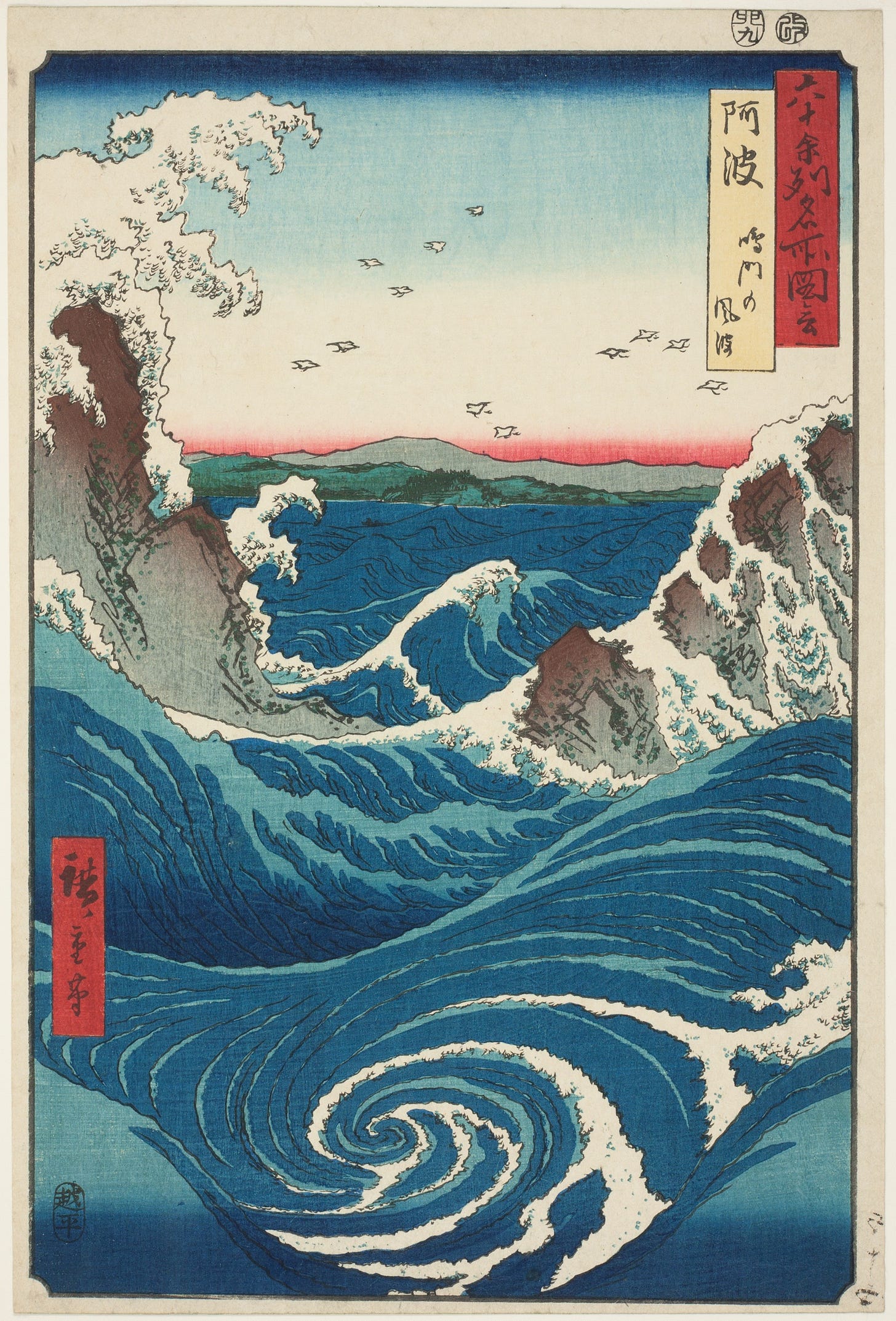

In our first year of practice as a Sangha, we focused on this very thing—the safety of the ground. At first it was literal and relative. We practiced sensing the earth beneath us, noticing gravity's pull, and tuning into the truth that in this very moment, we are safe. Over time, that practice began to rewire me. I learned to drop below the whirlwind of thoughts, to settle my body into the bedrock of the earth.

As our practice matured, meditations expanded beyond the relative, present moment safety of dirt and rock and physics to a kind of safety that didn’t deny the presence of danger, but coexisted with it. I found fundamental safety–the connection to a vast, infinite, ever changing tapestry of existence. In Buddhism this might be called "the ground of being," "dharma," or "pure awareness." I simply call it God.

Feeling fundamental safety doesn’t mean my animal body is blind to threat. Quite the opposite. Reflexes still fire. My body still reacts when needed—heart racing, breath changing, muscles bracing. But I now recognize that fundamental safety isn’t about removing all danger or fear. It’s about knowing who I am underneath it. It's a grounded presence that allows me to meet life as it is.

I think of elite martial artists or first responders. They don't deny danger or suppress fear. They train with it. They move through it with skill and clarity so they remain effective. There's a kind of clean alertness that arises when fear isn't distorted by panic. Like meditation, their training teaches them to stay present with intensity rather than being overwhelmed by it. They learn to feel fear while maintaining access to clear thinking and skillful action—the same quality of grounded awareness that emerges from contemplative practice. Like the fierce clarity of anger when a core value is crossed—not the muddled anger of ego pain, but the righteous "no" that protects what we love.

Meditation is that kind of training for life. It’s not the only path, but it’s been one of my mainstays. Somatic practices like breathwork, pendulation, movement, and free expression have helped too. These practices strengthen my capacity to respond to life wisely, with choice instead of reactivity.

Here’s a small but meaningful example.

One day in Boulder, I was walking through the foothills above town. Headphones in, happy music playing, I began to dance along the trail, a few yards above a field of picnicking strangers. Suddenly, a pang of self-consciousness swept over me. I imagined I looked ridiculous. Without thinking, I stopped dancing.

But then something gentle rose up: kind curiosity. A part of me asked, “Liz, sweetheart, why did you stop dancing? You love to dance.” My body told me: tight chest, clenched jaw, fluttery belly. Ah yes—fear of judgment. Fear of looking foolish. My ego didn’t feel safe.

I asked myself kindly: “Are you in danger, sweet girl? Will dancing harm you or anyone else?” I looked around and laughed quietly. No. Not at all.

So I turned the music up and started to sway again. Insecurity rose—I welcomed it. A wave of panic came—I slowed to a gentle movement. I breathed deeply, grounding in the solid earth and open sky, opening myself up to the field of awareness. Then, I danced like a 20-year-old at a rave. Unapologetically. Joyfully. Freely. Right there in plain sight of dozens of strangers.

This is what fundamental safety feels like. It’s not bravado. It’s not denial. It’s the deep permission to be, even in the face of discomfort.

Another example–this past weekend at my 30 year college reunion dinner, I carried a plate piled with food from the buffet line to my table. Somehow, I miscalculated where my seat was and I sat down onto thin air, falling smack onto the ground, creamed chicken and pasta spilling all over my dress. I actually laughed. It felt silly, slightly embarrassing, but not devastatingly so. I cleaned myself up and carried on with the evening. In years past, embarrassment and shame would have stayed with me throughout the night. This time though, it rolled off me. The fundamental security I've cultivated remained untouched. It carried me.

To be clear: relative safety is essential, and not everyone has access to it. Children grow up in unsafe homes, neighborhoods, or systems. Their nervous systems adapt in brilliant, protective ways—people-pleasing to avoid attack, staying small to stay hidden, acting out to feel connection, numbing to survive. Even if they find relative safety in adulthood, those early patterns often persist, cycling through fear long after the danger has passed. And many people around the world continue to live in truly unsafe conditions, where violence and meeting basic needs is a daily struggle. We must continue to work towards a world that is safe for everyone.

For those dealing with past trauma or current unsafe conditions, accessing fundamental safety often requires additional support—therapy, community, sometimes medication. The nervous system may need specific healing before it can settle into deeper ground. For people living in dangerous circumstances, the work isn't about transcending vigilance but about finding moments of inner refuge that can coexist with necessary protective measures. This isn't spiritual bypassing or suggesting that meditation alone can heal complex trauma or change situations. Rather, it's recognizing that even in the most challenging circumstances, there can be glimpses of an unshakeable essence—and that these glimpses, however brief, can be profoundly sustaining.

This is why both kinds of safety matter.

Relative safety provides the essential conditions for thriving. We need food, shelter, dignity, and protection from harm. But even relative safety is not absolute. Life is fragile. Accidents happen. Systems fail. Our bodies age. We die. In this way, relative safety is always conditional. We must work to strengthen it—for ourselves and one another—while also recognizing its limits.

Fundamental safety, by contrast, is not conditional.

It doesn’t depend on circumstances. It is a deep inner knowing, a felt sense of belonging to something vast and mysterious that holds us all. It is the stillness beneath the storm, the thread of being that remains unbroken. It’s what allows us to move through life’s changes with grace, presence, love.

Together, relative and fundamental safety support our capacity to live fully.

One without the other is incomplete. Without relative safety, it can be difficult—if not impossible—to access the deeper ground within. And without fundamental safety, even the best circumstances can feel thin, hollow, or insecure.

But when both are present—when our bodies feel safe and our hearts remember who we really are—a kind of wholeness emerges.

We become more free. More resilient. More alive.

We can laugh when we fall.

We can dance, even when watched.

We can breathe into fear and still stay open.

We can meet the world, uncertain as it is, with presence.

**I highly recommend Daniel Thorson’s excellent substack The Intimate Mirror. He talks eloquently about safety and attunement.**